- Have any questions?

- +34 951 273 575

- info@allaboutandalucia.com

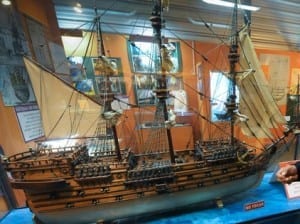

Raising centuries-old ships can reveal a treasure trove of information about our buried past

Coast with the most

February 21, 2017

Manilva over millennia

February 22, 2017 AN operation to raise a 250-year-old British ship from the waters around Uruguay is set to begin on February 10.

AN operation to raise a 250-year-old British ship from the waters around Uruguay is set to begin on February 10.

As the Olive Press reported last week, the move will be spearheaded by Argentinian treasure hunter Ruben Collado, who hopes to find as much as £1 billion in gold bullion on board.

But Collado is interested in more than the money. The sinking of the Lord Clive was an important historical event, he says, and raising it will allow us to see ‘the true magnitude of the story’.

This is a story of why a British ship was sunk by Spanish cannon fire while defending a Portuguese colony on the coast of Uruguay, 254 years ago.

It is a story of colonialism, alliances and declarations of war which changed the course of world history and helped to shape the countries that we know today.

The Lord Clive was sunk while attacking Colonia del Sacramento, a Portuguese fort built in 1680. The area formed the frontier between Portuguese-held Brasil and Spanish-controlled South America and was the subject of a continual tug of war between the two colonial powers. It changed hands four times in eight decades; and then a fifth time in 1762, when the Spanish retook it in the Fantastic War.

The Lord Clive was sunk while attacking Colonia del Sacramento, a Portuguese fort built in 1680. The area formed the frontier between Portuguese-held Brasil and Spanish-controlled South America and was the subject of a continual tug of war between the two colonial powers. It changed hands four times in eight decades; and then a fifth time in 1762, when the Spanish retook it in the Fantastic War.

This war was fought between Spain and Portugal from 1762 to 1763 but, as there were no major battles, it was nicknamed ‘fantastic’

This ‘Fantastic War’ was a part of the Seven Years’ War, which was fought between 1754 and 1763 primarily between Britain and France, on a range of frontiers across almost every continent. Britain did badly at first but came out well in the end when, as British statesman George Macartney wrote in 1773, Britain owned a ‘vast empire, on which the sun never sets.’

Spain and Portugal were both initially neutral, but this changed when King Charles III took over as the new ruler of Spain in 1759.

Spain and Portugal were both initially neutral, but this changed when King Charles III took over as the new ruler of Spain in 1759.

Concerned that Britain might come out of the war a stronger colonial power than Spain, he signed the Bourbon Family Compact with France in 1761 (both ruling houses were members of the Bourbon family), bringing the country into war with Britain in 1762.

Spain then allied with France to attack Portugal which, though neutral, had long been an important economic ally of Britain’s. Hoping to distract British troops from attacking French soil, Franco-Spanish forces swiftly invaded both on Portugal’s European frontier and in its South American colonies. Colonia del Sacramento fell in 1763.

It was at this point that a group of British merchants stepped in, deciding that an attack on the Spanish-held territory would be useful to the nation and financially beneficial to businessmen. The East India Trading Company bought the Lord Clive (formerly the HMS Kingston which they rechristened after the Commander in Chief of British India), and sent troops and finances from London to South America, picking up Portuguese allies on the way.

The plan was to attack Montevideo, but the waters were too shallow so Captain Robert MacNamara resolved to take Colonia del Sacramento instead.

The plan was to attack Montevideo, but the waters were too shallow so Captain Robert MacNamara resolved to take Colonia del Sacramento instead.

The ships took up position on January 6, 400 metres from the shore. This was too close and the Anglo-Portuguese fire aimed too high and missed its target. The Spanish forces were better prepared than MacNamara had expected, and cannons hit the Lord Clive, exploding the magazine and sinking the ship.

Over almost before it started, 272 people drowned but there were only four Spanish casualties.

The Lord Clive lies in just 16 feet of water, but the Spanish dropped rocks on its hull so that the rest of the Anglo-Portuguese contingent couldn’t refloat it.

The Lord Clive lies in just 16 feet of water, but the Spanish dropped rocks on its hull so that the rest of the Anglo-Portuguese contingent couldn’t refloat it.

The Treaty of Paris returned Colonia del Sacramento to Portugal in 1763. But in a political game of ping-pong it passed back into Spanish hands in 1777, was subsequently returned to Portugal and owned by Brazil for a while, before Uruguay was founded in 1828.

The British, however, never had another look-in.

As Collado points out, the sinking of the Lord Clive had a big impact. “If that ship had not failed in its attempt to retake the city of Colonia del Sacramento, today we could be speaking English throughout Latin America.”